Notebooks for The unproductive jobs*

Gerardo Naumann

This work is dedicated to the love that Julieta Bonaiuto and Mauro Petrillo have given me in these recent years. Though I can no longer tell how many years it has been.

* Recently, I organized my works in a series, more or less by subject. In doing so, I feel like a visiting doctor who organizes his patients by neighborhood. The Unproductive Jobs is part of Series 3, which also includes The Pickpocket. In both pieces, I worked around the idea of appropriation, the idea of what to do with things we take from others. There are some mentions of the working process of The Pickpocket in these notes. The plays hold a dialogue between each other in a fairly mysterious manner.

My working processes have various stages. The first is confusion and uncertainty. It is inhabited by vague ideas, tracings for possible journeys, some concepts, and a unique attitude: of letting things enter. In this stage I am always alone and observing everything. The second stage is characterized by a light tendency to organize things, to begin to remove the extras and design a first plan of action. At this point, I am joined by one or two people. The piece begins to build its strength.

The third is execution and production. It has the shop of a distant gaze and group work, and I only think of concentration. These notes are from the first and second parts of the work.

2014

In Marseille, with Industrial Work. Rodrigo sends me an email to ask if I want to have lunch at his house in Montpellier. I say, yes. In the train. The rhythm of the melancholy, of that which is studied. That which is studied can assume the risk of velocity. There is velocity because there is a plan. The tracks are the plan. At 4:43 pm we will arrive at Montpellier. A man selling sodas walks by. He doesn’t know how many sodas he will sell by the time he gets to the last car. Various forms of the plan. I think about the form of the perfect plan. A play with the shape of a plan. A play that is like a map, like going along stepping on a map.

At Rodrigo’s house. I tell him that I am thinking about a play in which five thieves reveal and discuss a plan for robbing the bank that is across the street from the theater. Photos, models, blueprints, cigarettes and music. We cut off slices form a ham leg.

2015

March 12

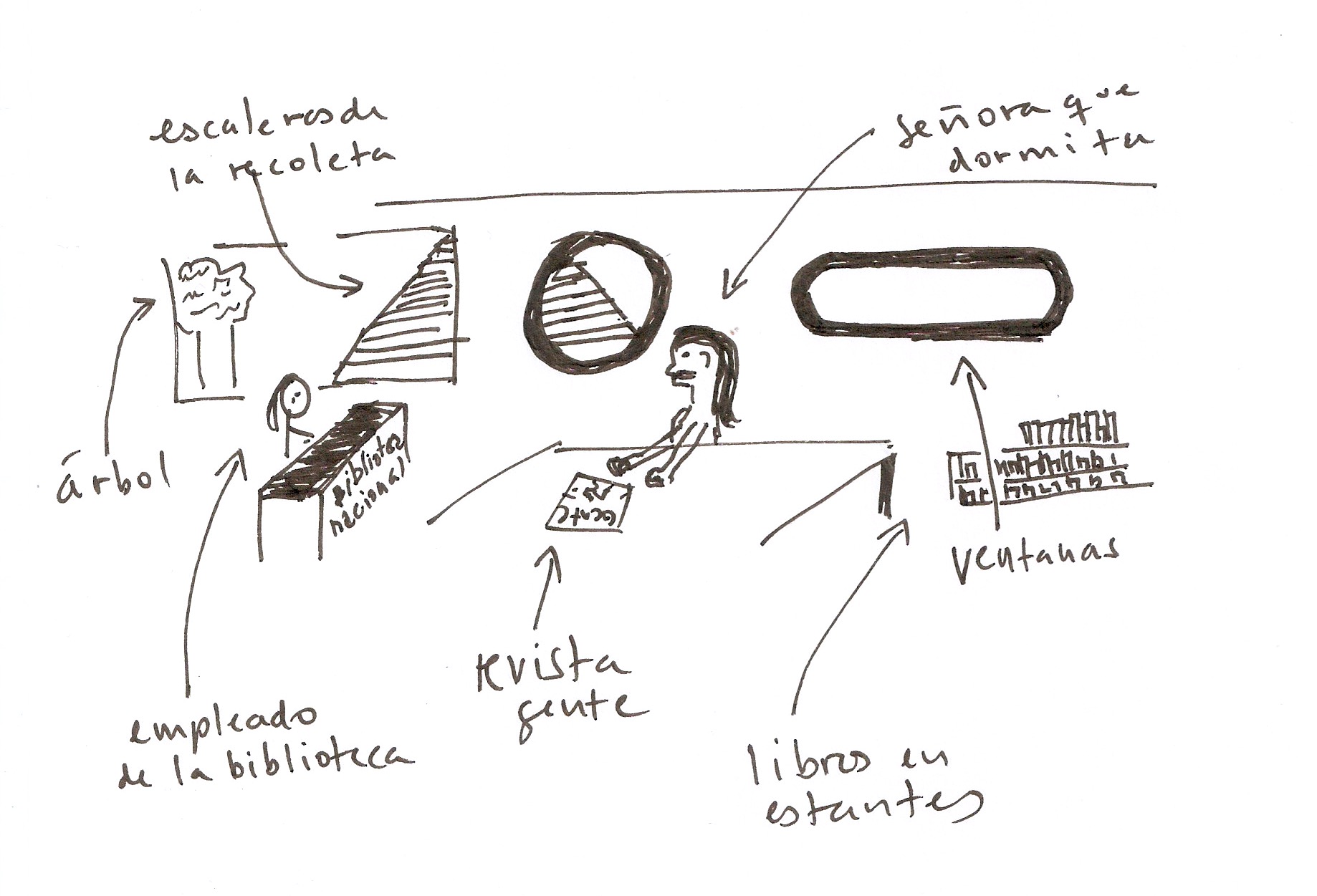

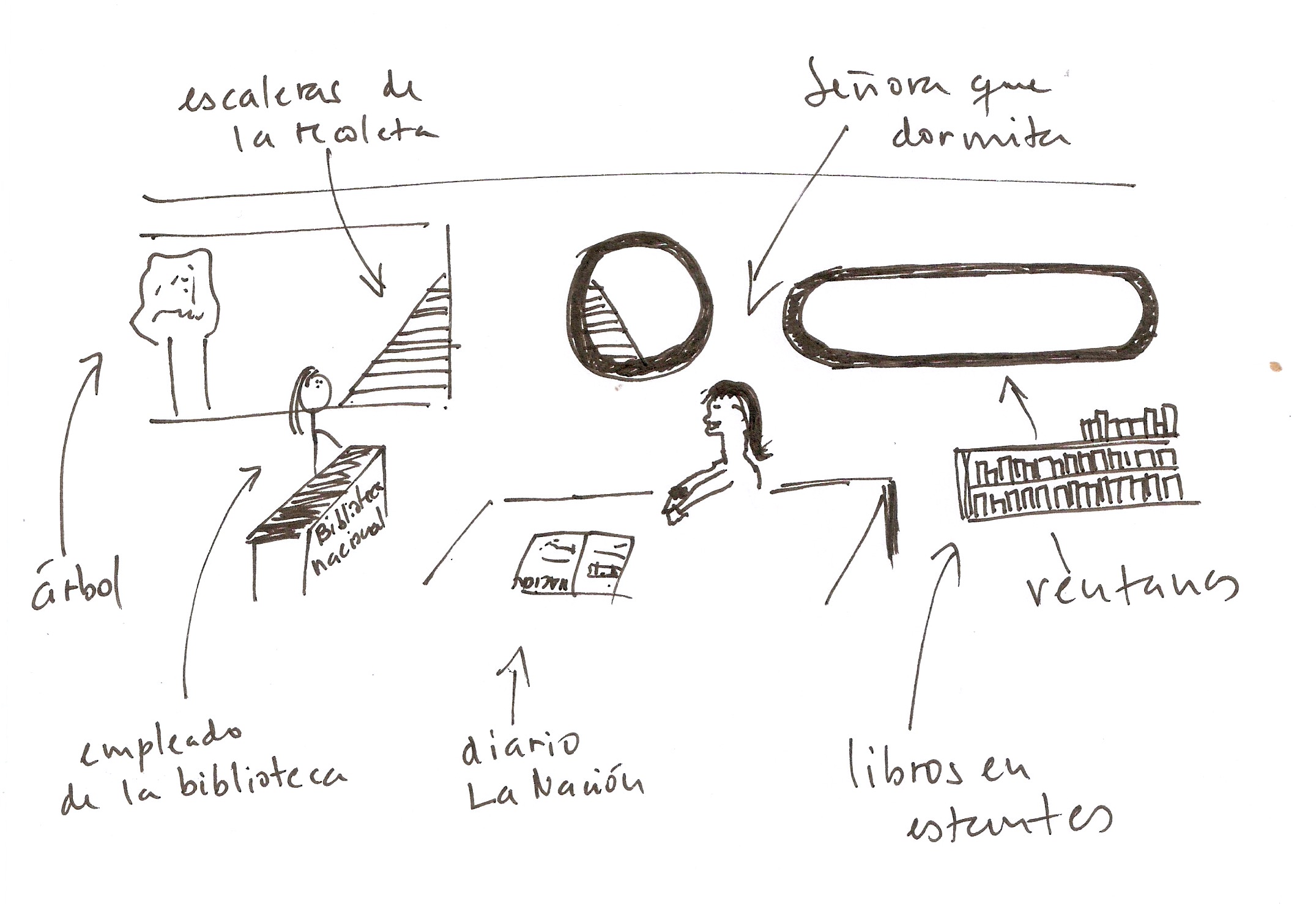

Days in the national library. In front of me, diagonal, a woman is sitting. She is wearing a long coat and a small scarf. Pastel colors. She is reading the newspaper and magazines and takes little naps while she sits at the table. One day, while she was sleeping, I take a photo of her and a few days later I take another. I rob her image from her. I look for the photo on my computer, but cannot find it. I draw her.

July 30

I am looking at photos of Poland, from the time I was workin on the performance Workers leaving the Factory. I find some photos of two guys playing badmington (is that how it is spelled? four years without internet so far). The three photos seem to be taken in the same place, but it could be that the two of them are not playing each other. They might even be in different places. The third photo seems to deny this, but this could also be part of a plan. The editing that creates an illusion. The thief as editor. Make a cut, but when?

October 22

In The Pickpocket, the actors’ voices travel via satellite and are reproduced by the actors on the sidewalk. Everything is a promotion, everything is cheap, everything is given away, stolen. Robbery as a gift, the gift as something robbed. No letting yourself give away anything.

October 25.

A group of rebels enter a theater in Chechnya in 2002. They interrupt a play and take 600 people as hostages and have the world in suspense for a week. In the photos, the moment that they go up on the stage. For a moment the actors believe that what is happening is part of the fiction. The raid takes a fictional form. The raid is not continuous with reality.

November 12

I am working on The Pickpocket. I go to toc toc and ask if I can take photos from behind the stage. First I take pictures of the actors. Everyone is looking at a center. Like in sports, there is no outside. The center summons.

The technicians show me a small hole through which I can spy on the audience. I look at the people. The spectator seems to be in a straightjacket. The spectator as character. Trapped, captivated. The captive looking at the actors that look at the center. People go to the theater to watch people who are focused. To look at people who are watching a center.

During a robbery there is no outside. The thief as the creator of a center. A play that seems to be without a center, though in reality this does not exist.

2016

April 26

The production of the play is confirmed. The tentative title is The Assault. To take a space by assault. I am thinking about this idea. What I like is less important than the feeling that I have been assaulted by the idea. No to the ideas that I like. Yes to the ideas that assault me.

May 3

The casting. I could go out on the street and let a thief mug me and during the mugging convince him that we could start meeting to rehearse. He could return what he stole from me or I could discount the cost of these – used – objects from his fees for the rehearsal.

May 5

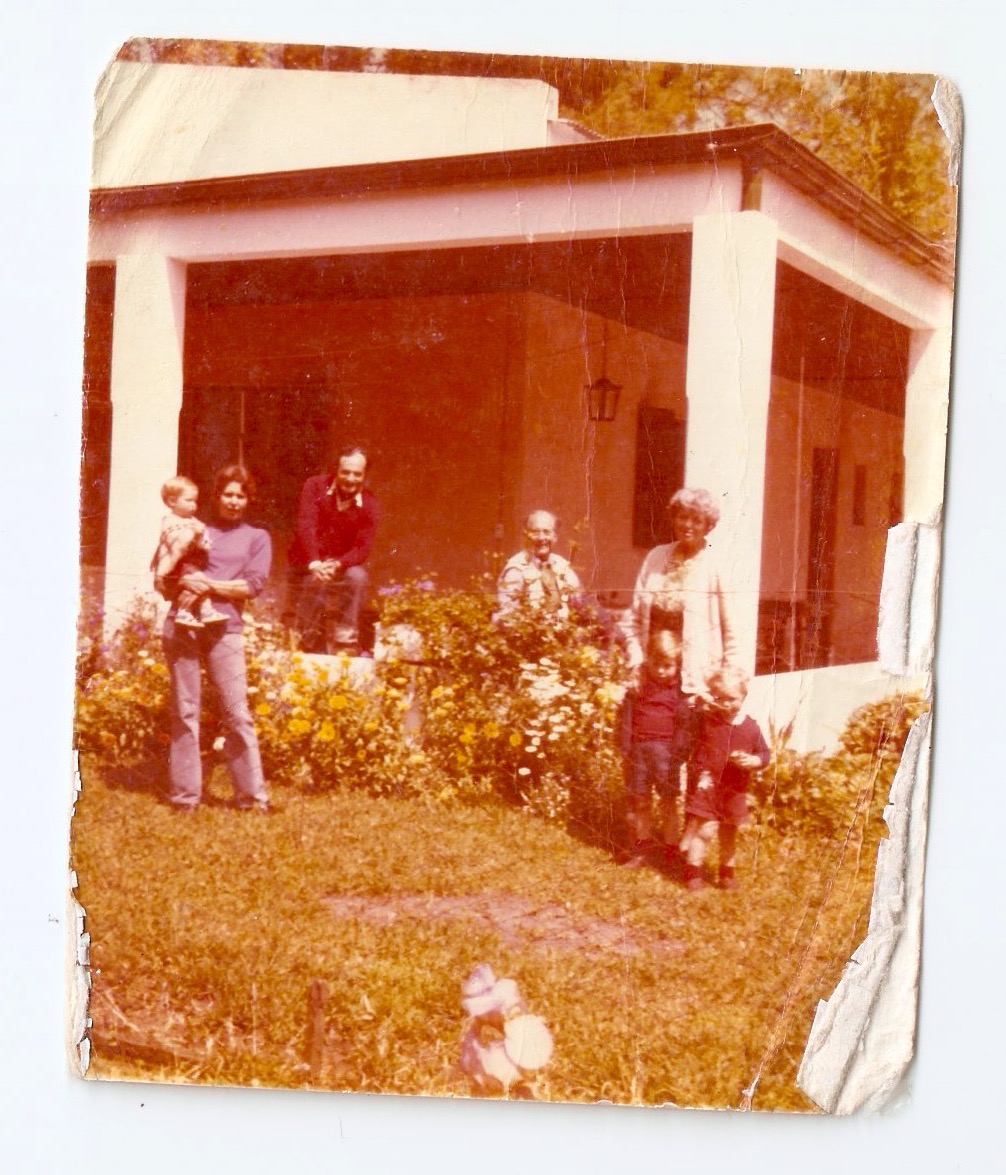

Four years ago, on a May 5, my father died. In the photo, he looks so young. This is in the gallery of the country house where I was born and lived until I was five years old. We would spend the whole day there. My father is the one who has his foot on the little wall.

My dad liked working and he liked the people close to him to work as well. When we were little we would do simple tasks. After breakfast, we had to work until 10 a.m. Here I am washing the doghouse. I wash the walls and the roof and then the insides. Inside there is a lot of dog smell. I don’t know if washing the doghouse does any good, but it has to be done.

In the summer we go on vacation. From the beginning of December until the end of March we were there. In the country, there are a thousand things that need to get done. The big threat is nature itself. The grass grows and needs to be cut. The horses run and we need to put up a fence so they don’t run too far. The water goes into the ground and we need to make a mill to bring it back up to the surface. The cows drink the water and we need to bring more of it to the surface. And so on.

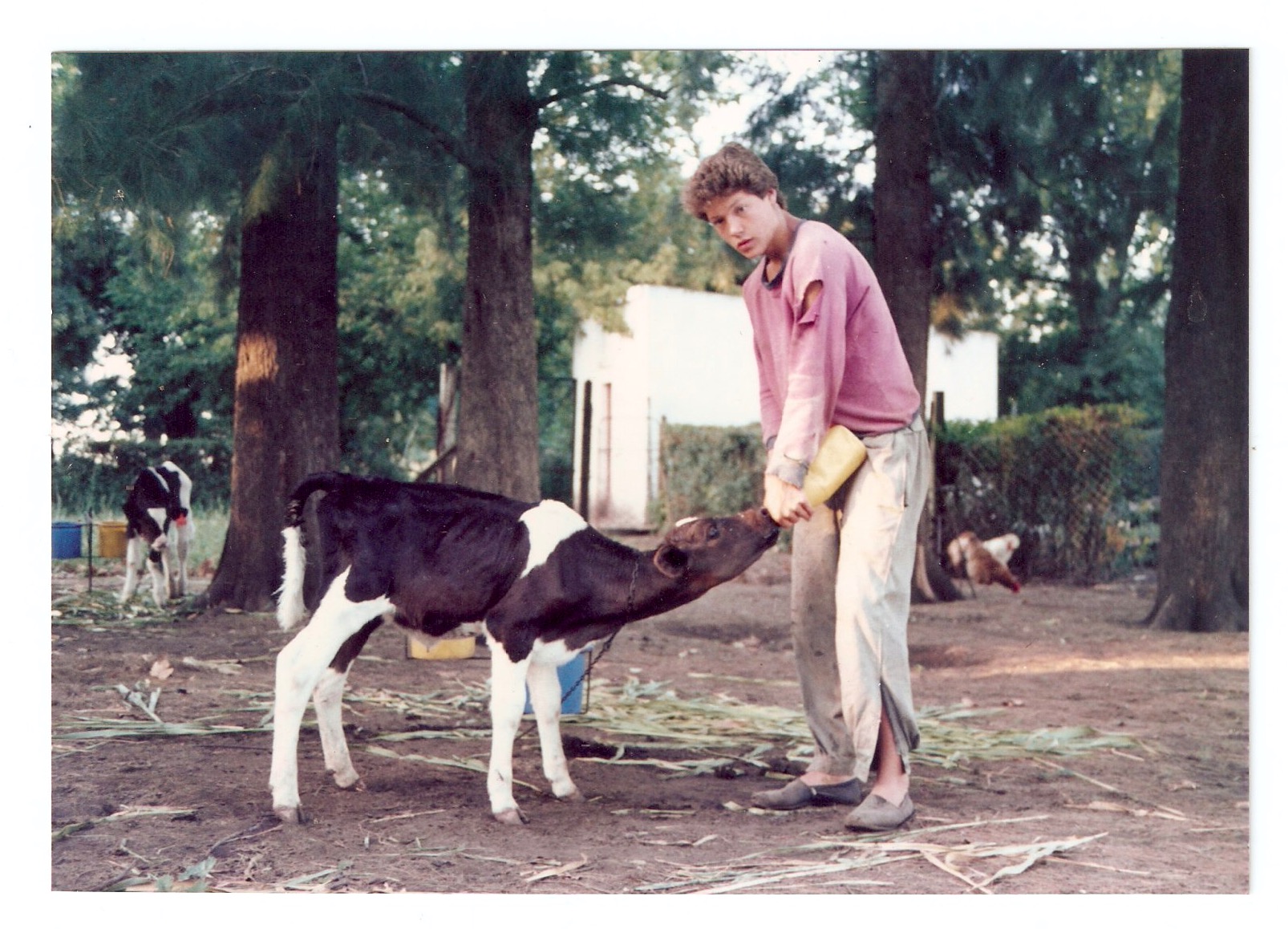

In this photo we are giving milk to the orphaned (“gaucho”) calves. They are called gaucho because they were separated from their mothers a few weeks after birth. The mother can’t nurse them because she is being milked. The calves are given artificial milk. That’s why we use homemade feeding bottles using the finger of a rubber glove placed over a bottle that was used for bleach originally. We rinse out the bleach bottle a lot before using it.

Every morning, fairly early, we gave milk to 150 calves. When I am working, I don’t realize that I am with a calf. Like it is something I do every day and so it becomes mechanical. The things that bother me, bother me less and less, and the things I like, I like less and less. Every morning a lot of smoke gets in my eyes. Every morning I scratch myself and think every morning, this smoke. The calves escape and I have to go after them, wearing my rubber boots. The boots are heavy, but I am not thinking about the weight of the boots, because yesterday they were just as heavy, and they will also be heavy tomorrow.

At work, I put my attention to what is new. But what is new is not the new thing, in capital letters. Not I nor anybody was waiting for these lands to suddenly be expropriated, or that the calves would nurse themselves or that the mothers would bite through the fences and come to recover their children. The new thing that we wait for is something minute. It is on the border of being imperceptible. Working in the field during this time, I realize that the smoke changes its odor, depending upon whether or not dew had formed on the firewood overnight; the leaves of the trees make a certain sound when they move, depending upon whether they are blown by a very light breeze that comes from the south; the calves all react more or less the same way, but really very differently to the same stimuli, as if they had something like a personality. Working, doing the same thing every day, I realize that there something like levels. That which is the same every day, stays anchored in the first level. On top of this there is a second level, that of that which is new. The second level happens as soon as the first is completed. So that the differences can be noticed, things have to be always the same.

At work, I have down time when I do nothing. For example: a calf takes five minutes to drink his bottle. During this time there is not much to do. You can see it on my face. In the photo, I seem dreamy, in some far away time and place.

Since I was more or less 12 years old, I have been saying that I want to study agronomy. During my last summer in high school, my classmates rented a house in an area for summer vacations and asked if I wanted to go. Since I really didn’t want to, I said no. My father spoke with a friend of his and got me a job working on very big farm in Santa Fe. The farm was called Las Taperitas. At this farm they make all the products for Ilolay. This is the entrance to the farm.

The farm is big and when I arrive nobody pays much attention to me. The owners aren’t there and I was left a bit on my own. The foreman put me to filling the silo. The silo is filled in summer. You cut corn or sorghum or grass and pile it up. So that the mountain takes form, you have to distribute what you cut with a pitchfork. So: the machines cut the grass and they throw it off the top of the trucks, the trucks bring it and toss it, a group of men spread the grass around with pitchforks forming the mountain and, -finally-, a tractor flattens it out. Having the tractor pass over it is important because it takes the air out of the mountain of grass. This was the grass does not go rotten, but instead slowly ferments. By the winter it reaches a perfect state and for the cows it is like eating caviar. In this photo, you can see the silo and the tractor running over it.

And in this photo you can see the tracks carrying the grass.

The harvesting work of the silo in Las taperitas is done by a company, a small company that is. It is managed by two guys with big beards who are kind of phonies. To keep costs down, they employ people who are finishing their sentences in a state run prison. Since they are almost done serving their time, the state lets them go out and work. I’m certain they are paid two pesos, but the guys take the opportunity to send some money to their families.

The work is done in eight hour shifts and goes on 24 hours a day. Sometimes we have to do two shifts in a row because someone is sick. These days it is 16 hours straight, without stopping. The workers smile when they announce extra hours or a double shift, because this means a bit more money. That summer I lived for the first time, with people who were in jail for robbery or worse. They don’t talk about what they did. I figure it out bit by bit, as if through the backdoor.

We had a lot of fun that summer and I forgot forever that image of the criminal = insecurity. While we were standing on the silo, spreading out the grass with our pitchforks, sometimes we were silent and we wouldn’t speak for hours. The work there is very tiring because the mountain of grass is soft and your legs sink into it while you work. Being silent is a way of saving energy. The silence is a fundamental part of the manual labor. We work and drink water or wet our faces, the nape of the neck, the hair, and get back to work. Hours later, suddenly someone says something. And whatever is said seems to come from the beyond. A dog that was born without teeth, a person who speaks without moving his mouth, a refrigerator that one day stops opening and has to be thrown out, an exotic food that is made with dirt, whatever. That summer I learn exaggeration and the laughter that it leads to.

A conversation starts with something simple, and an instant later it flips over a few times in the air, turns around and becomes something else. This misshapen thing mutates, then becomes normal and then deformed again. When I think it has reached its highest height, the conversation flips again and we are floating in the beyond.

Everything takes place where we are: the top of a silo in the middle of January in which it is 40 degrees Celsius in the shade. The silo is the factory of meanings. What makes it absurd is the context, that we are speaking of those things there. There is no real ingenuity, no creation. There is just understanding where we are.

One of the men’s names is Hugo, bet everyone calls him El lagarto (The Lizard). He escaped from a number of jails and is now a bit older. That summer, The Lizard taught me how to smoke. As if offering me a gold ingot, he would share some of his cigarettes with me, and we sat on the roof of the tractor looking at the stars. Below us everything was vibrating and there was so much noise we couldn’t even hear what the other said, but all the same we were good and the summer passed quickly.

Before everything was over, I wanted to take a photo of my work companions, -these thieves in the last months before they returned home-, but they didn’t like the idea much. That day I thought that maybe it was because they didn’t want to be seen. Not everyone wants to be seen when they reappear. Even I don’t smile much in photos. Mistrust is a motor.

May 10

Maxi worked with me on The Factory and then on Industrial Work. I call him on the phone. His voice is quiet and he speaks with the rhythm of the machines he works with. I ask if his knows any thieves. He says he does. He tells me about a guy called Romeo.

In the jail in Ezeiza there is a psychiatric program. A group of psychiatrists takes care of the inmates 24 hours, 365 days a year. He gives me the contact information for the person who coordinates the activities. I call her and tell her what I want. She says to go there. Maybe, I can get into the jail with the help of the people of that program. The inmates must have contact with the people outside. Questions: how do the people inside communicate with the people outside? Does a prisoner call his mother and tell her what he ate? What they brought him for breakfast?

May 12

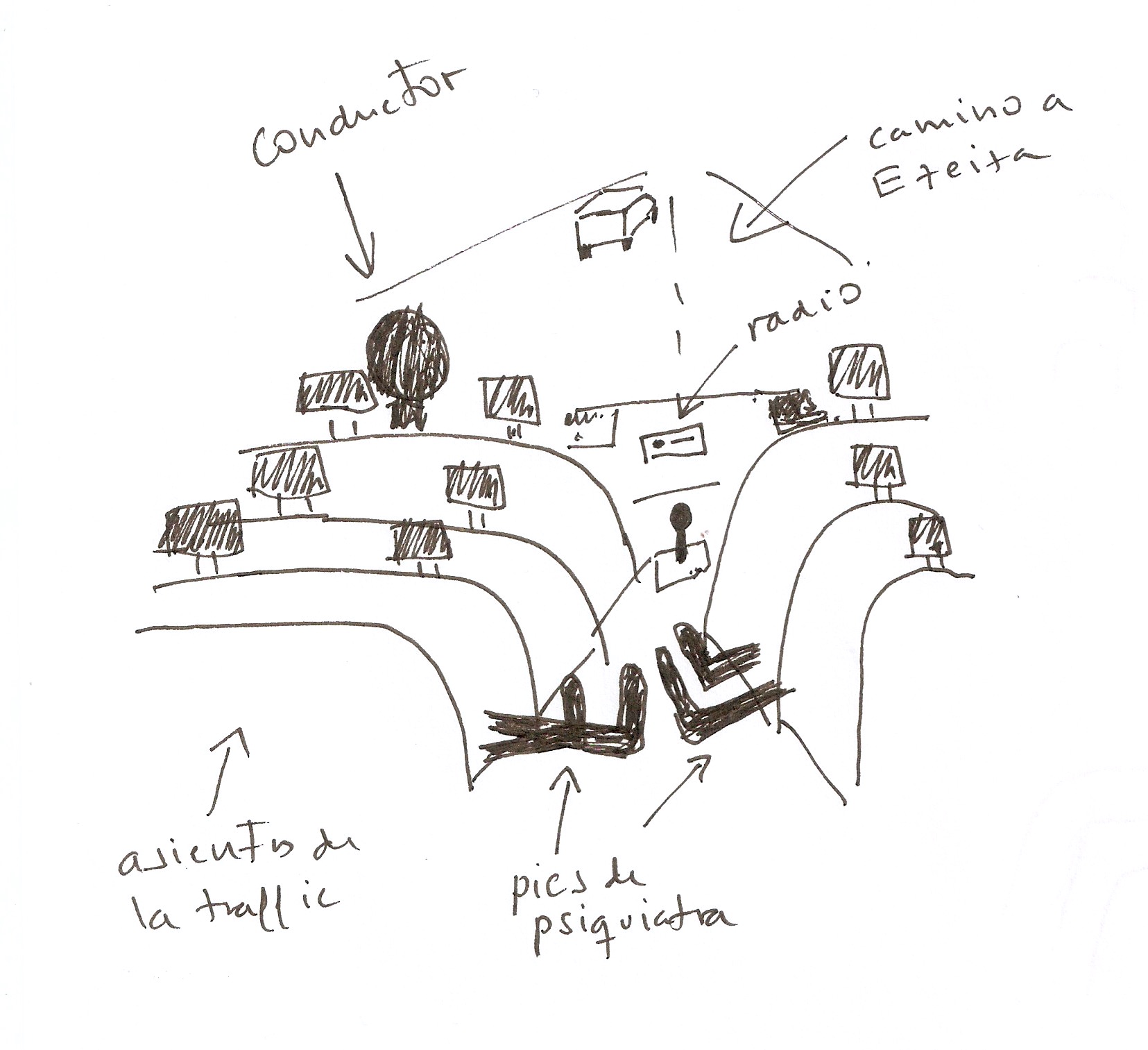

I travel to the jail in Ezeiza. The van that brings the psychiatrists leaves at 8 a.m. It is a white Trafic van with a number of seats. I go in the back seat. From there I can watch what happens in front. A psychiatrist is eating an apple. Another is sleeping. Another sends messages from his cell phone.

The van has polarized glass. The psychiatrists are chatting about things. Then they stretch out on their seats and go to sleep. From the backseat I can see feet sticking out from the shorter seat. Here is the drawing I made of them.

.

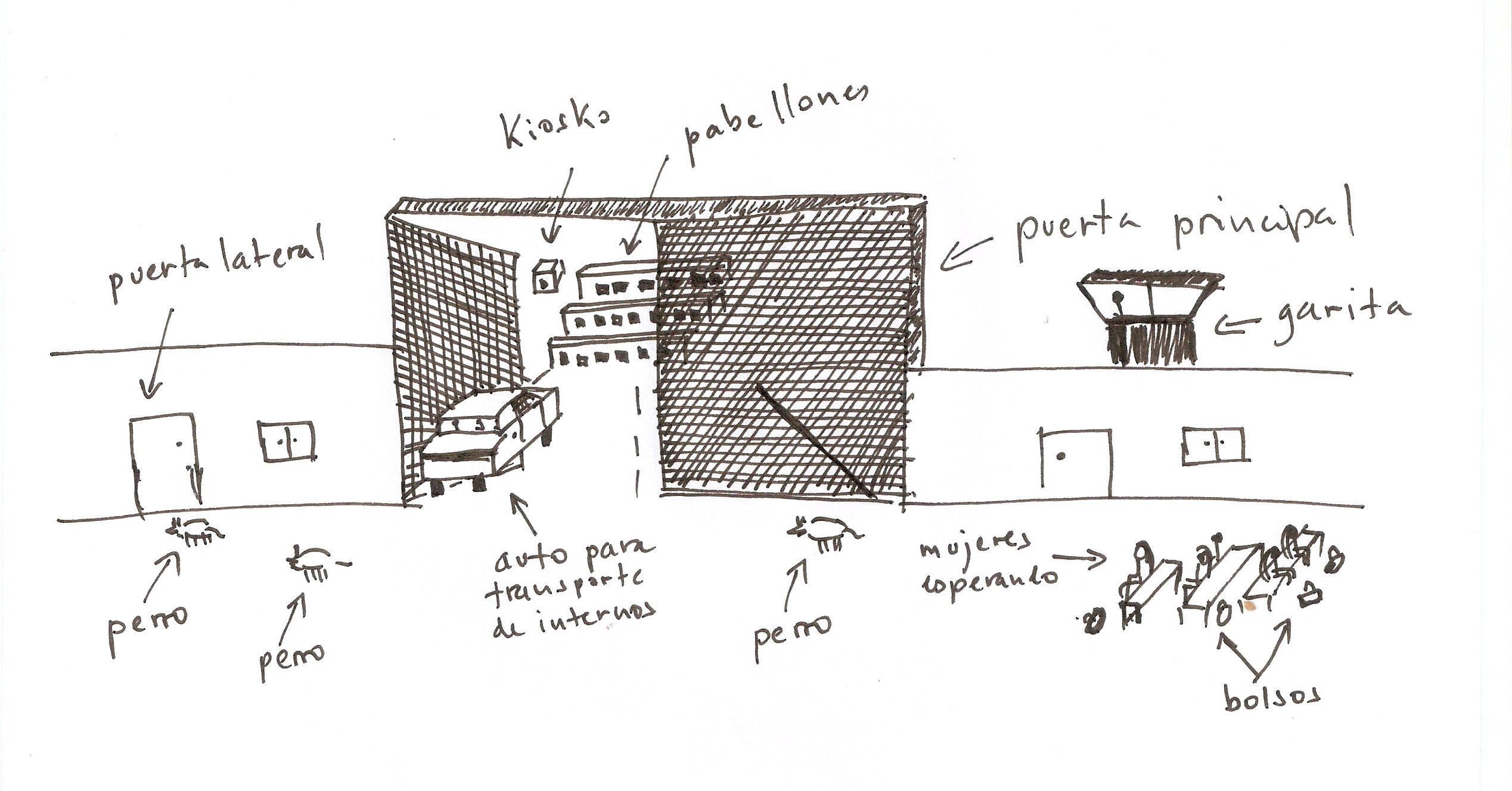

At 9:00 a.m. we get to the jail. The front door is the main characters of the scene. Through here people enterand leave.

The psychiatrists walk, crossing the parking area of the entrance. I follow them. We go to some smaller side doors. In front of these doors there are dozens of women. They hope they can enter to see their sons, husbands, boyfriends, lovers, friends, brothers. There are dogs, lying on the ground, among the legs and bags of the women. For a moment, I think they are the dogs of the inmates that, - like when they are waiting in front of the supermarket -, spend years there looking at the door and smelling the people to come out to see if one is their owner.

The side doors of the jail are slightly open and they look like any normal door. We go in. They ask for my ID. We walk down a long hallway which a lot of wind is blowing through. At the end is another door that is also open. The hallway is wrapped around me. Almost at the end, before reaching the door, I see that there are some doors on the side of the hallway. These are the offices of the police of the jail, the correctional officers. All of them see us and greet us, saying good morning. I think about the tunnels that the inmates dig underneath them in order to escape from here. We are inside. The inside is an open space, enclosed by the outer walls of the prison. There are streets and sidewalks that connect the various cellblocks there, one behind the other, with about 50 to 70 meters between one cellblock and the other. There are no cars circulating, but there are one or two parked. The first structure is a small sentry house. I go over to it and see that it is a kiosk. They sell candy, yerba mate tea, sugar, cigarettes, sodas, sandwiches and empanadas. I buy something. I feel strange paying, but what would it be like to not pay?

I follow the psychiatrists that bring me to the cellblock where they work. Leading to the entrance are some ramps that descend. A psychiatrist tells me it is built that was for ambulances and other vehicles. The inmates get hurt regularly: at times during fights, other times they injure themselves. The psychiatrist points to the ramp and says: so that they are well parked and manage to circulate easily. For something to brake it has to circulate easily.

Once again, we are standing in front of a door. This one is not open. We ring the bell. I hear a clicking sound, the electrical system that unlocks the door. The door opens. We enter a cellblock and again we walk by an office of correctional officers. All of them say, good morning, to us. After the office, another hallway, but not as long as the last one. At the end of the hallway, the first gate. It is open. It looks like the gates you see in the movies. White, with the paint worn. We reach the office of the psychiatrists. We enter. There is a group of five or six. They are waiting for the ones who just got there. We sit down and immediately start sharing mate tea and medialunas (croissants). Everyone is in a good mood. After a few minutes of socializing, they begin to read the report: what happened during the night shift, urgent cases. The inmates’ voices come to me through the psychiatrists. Mendizabal asks to see his mother. Asks if we can’t call her. Tobal hasn’t slept in three weeks. He has acid indigestion. I made him drink a glass of milk because he didn’t want to drink anything. Galvez feels that Galindo is harassing him. He asks to be moved to another cellblock again. He says that yesterday in the yard, he “growled at him”. The ones who worked the night shift prepare their bags and go. The ones who arrive in the morning get ready to start the day.

I talk to the boss in another office. I tell her about the play and say that, I don’t know what I have come to find. She says she has someone she wants me to meet. His name is Hernan. In a few months, he will be released. The meeting ends and one of the correctional officers comes to get me. He brings me to a room. There is a table and two chairs. The officer tells me that, to be sure I should sit in the seat closer to the door. He says, I’ll bring Ferrando. Ferrando is Hernan’s last name. We call him by his first name, but the justice system calls him by his last name.

Depersonalization.

While I wait, I look out the windows. All of them have iron bars. Ferrando enters and I put my hand out to him. I’m Hernan, he says to me. I am Gerardo, I answer. Hernan wears his hair slicked back, a pink polo shirt and a pullover on top of the polo shirt. Neat, he speaks slowly. He sits down, lights a cigarette and smiles. In the van back to the city, I fall asleep.

May 16

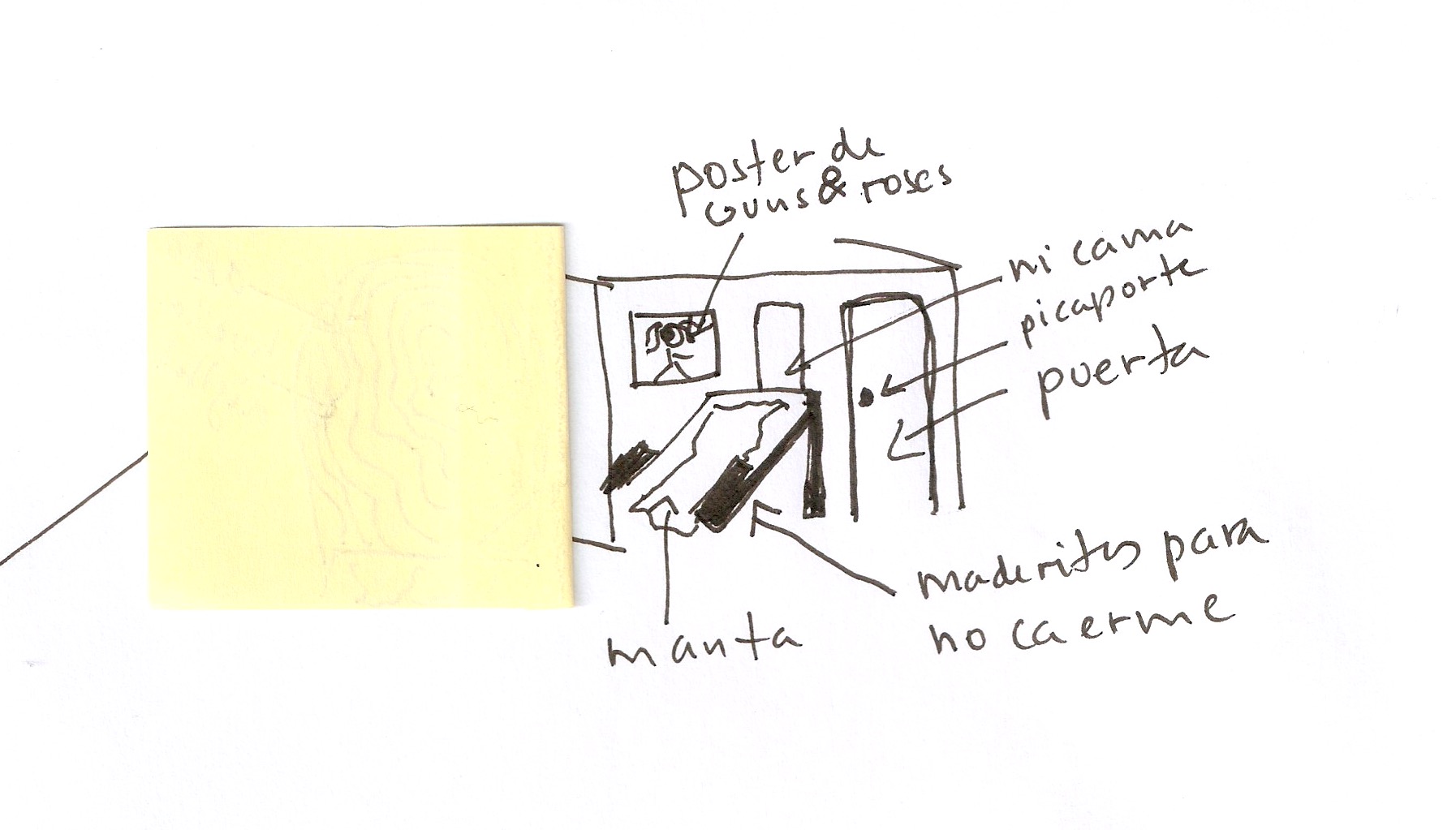

When I was a boy, I shared the bedroom with my two brothers. I slept on the top of a bunk bed. The bed had a slab of wood on one side so that I wouldn’t fall out if I turned over in my sleep. My bed was a cave. If I rest my head on the mattress I can’t see to the side because of the wood. Underneath, my breath slept and to our side, in a pull out bed, my youngest brother. My cave was inside this other cave, -the bedroom-, which I shared with my brothers. Every night, before going to sleep, my mother came to give us kisses. I would ask if she had plans to go out. I was afraid of the house being unguarded at night. My brothers made fun of me. At night I would wake up, go to the kitchen to see if my mother was still awake. Sometimes, I would find her with her head lying on the table, sleeping over her letters, the things she wrote, that she was preparing for her classes in the school. I would wake her up with my hand, startling her. She was exhausted and I sleepless, we would get in her bed and fall asleep.

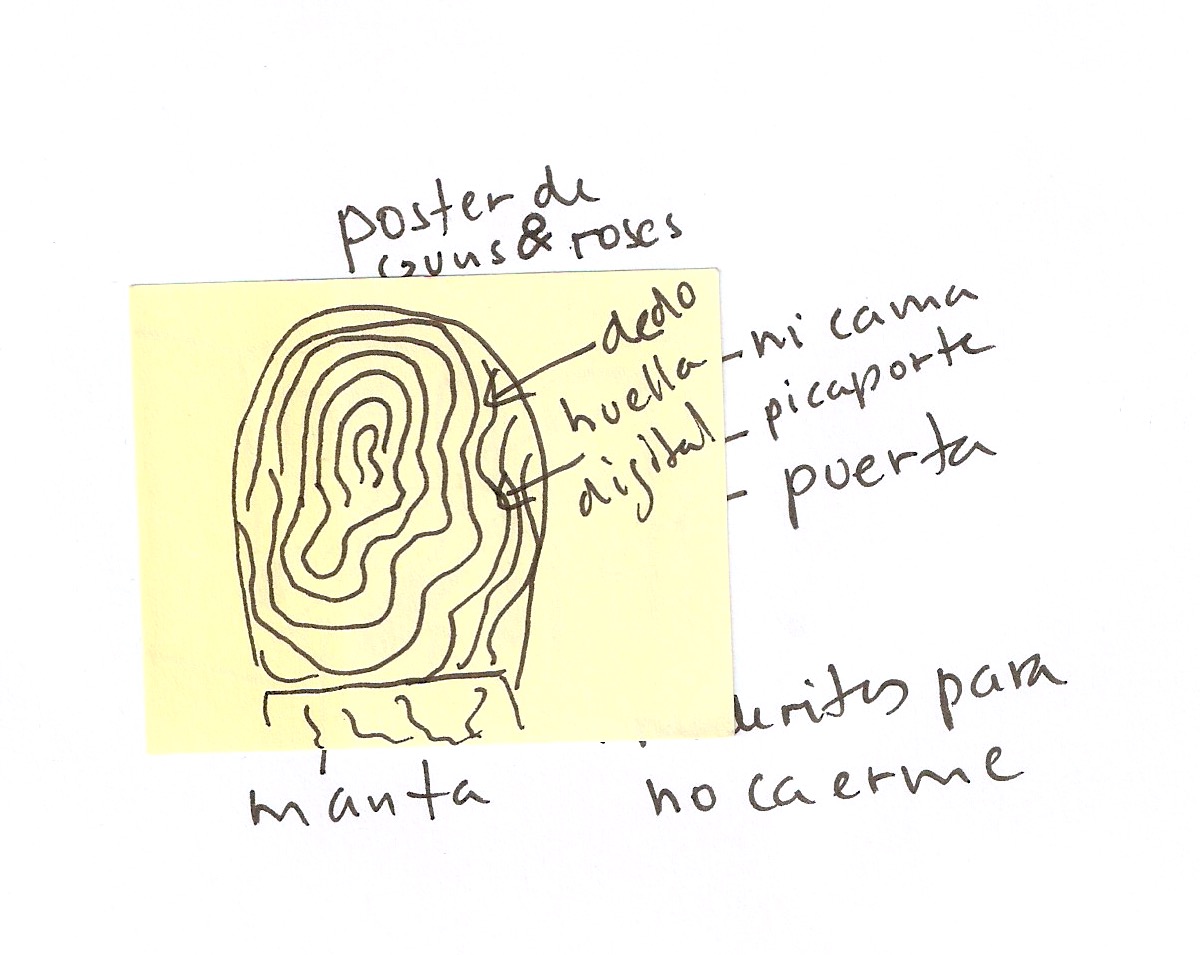

When my father would sleep in the house I was ashamed to go to my mother’s bed. Those nights I used a trick so that, -in case thieves entered the house-, they wouldn’t be able to find me. The trick consisted in closing my eyes and putting my thumb in front of my face. I would hide behind my thumb. You have to try it. At the time, it worked for me.

June 26

Second visit to the jail in Ezeiza. Hernan is uncomfortable today. He doesn’t know what I want. I tell him that I don’t know what shape the play will take. Close to Hernan in uncertainty.

The prison directs my gaze. When Hernan says the word match I hear it as if between quotation marks. I hear “matches”. The same thing happens with the word spoon, and with wire, or with any word. The jail, the building, the institution, adds something to what we say. When I was making The Factory the same thing happened. Work named within the factory is “work”. The architecture is a frame. It is built to make something visible. The jail constructs the figure of the thief. The play takes what is between quotation marks and transports it to the museum, to the space of art. I am only interested in that which is manufactured, that which is touched by culture, what is already recycled, that which is covered by the senses. Zero interest in nature, in primary materials.

June 27

I meet with Luciana Lamothe. There is nothing leftover and it seems that nothing is missing.

I think about the word code. The rule is what is written, the code is said. If the rules are changed, you must notify, you must let others know in writing. If the code changes, nothing changes. Everything is the same, and yet not. A play with the very same rules, but with a change of code.

June 28

Code. Don’t think of anything new for the piece. There is no change of law, but yes there is, a change of code. Everything already exists, but disrupted.

June 29

Hernan gives me a telephone number. It is the number of El largo, he tells me. Tell him I told you to call him. I called him. I told him you were going to call him. Who is he? I ask. A friend, he says. Oral communication as a way of doing things.

August 4

I found this photo in the street. I am surprised by the hardiness of the law. A caption written by hand. A space that could be a living-dining room. The thief does not meet The Law in capital letters, but rather the law in lowercase, armed with that which is there, a law that he himself sets up a bit, with what he brings. Is it too much to say that the thief sets up the law?

August 12

I meet with Hernan at Ezeiza. We talk about the various jobs he had before he began to rob. Everything comes together in a continuum. He doesn’t seem to perceive the jail. With his polo shirt and his hair slicked back he seems to be at a job interview. I call The Lizard. His voice is deep and he breathes like a smoke. We arrange to get together.

Neighborhoods I don’t know. I want a helicopter and a sleeping bag full of provisions.

August 13

Meeting at the house of The Lizard. Juli and I take a bug there. On the way we call him on the phone, but he doesn’t answer. We go all the same. He lives in a neighborhood outside the city on the ground floor of a building of monoblocs. We arrive, but he isn’t there. His wife says that she was looking for him. The Lizard has security cameras set up at the front door of his apartment. His wife says that he is almost never home. With his friends, she says. The family is the law, it is unyielding, written in blood. The friends are the code, that which is set up, what we have in common, the agreement.

About an hour later, The Lizard arrives. They call him Lizard because he is tall, more than 6’ 6”. Despite how cold it is, he is wearing a t-shirt. I ask him if he is cold and he says now. Del Potro is playing tennis on TV. We watch the game and talk. I ask him if I can take a photo of him and he doesn’t answer. I take it. Afterwards, I look at the photo when I get home. You can see the reflection of the television in his eyes. Don’t ask everything, instead do. Code.

August 17

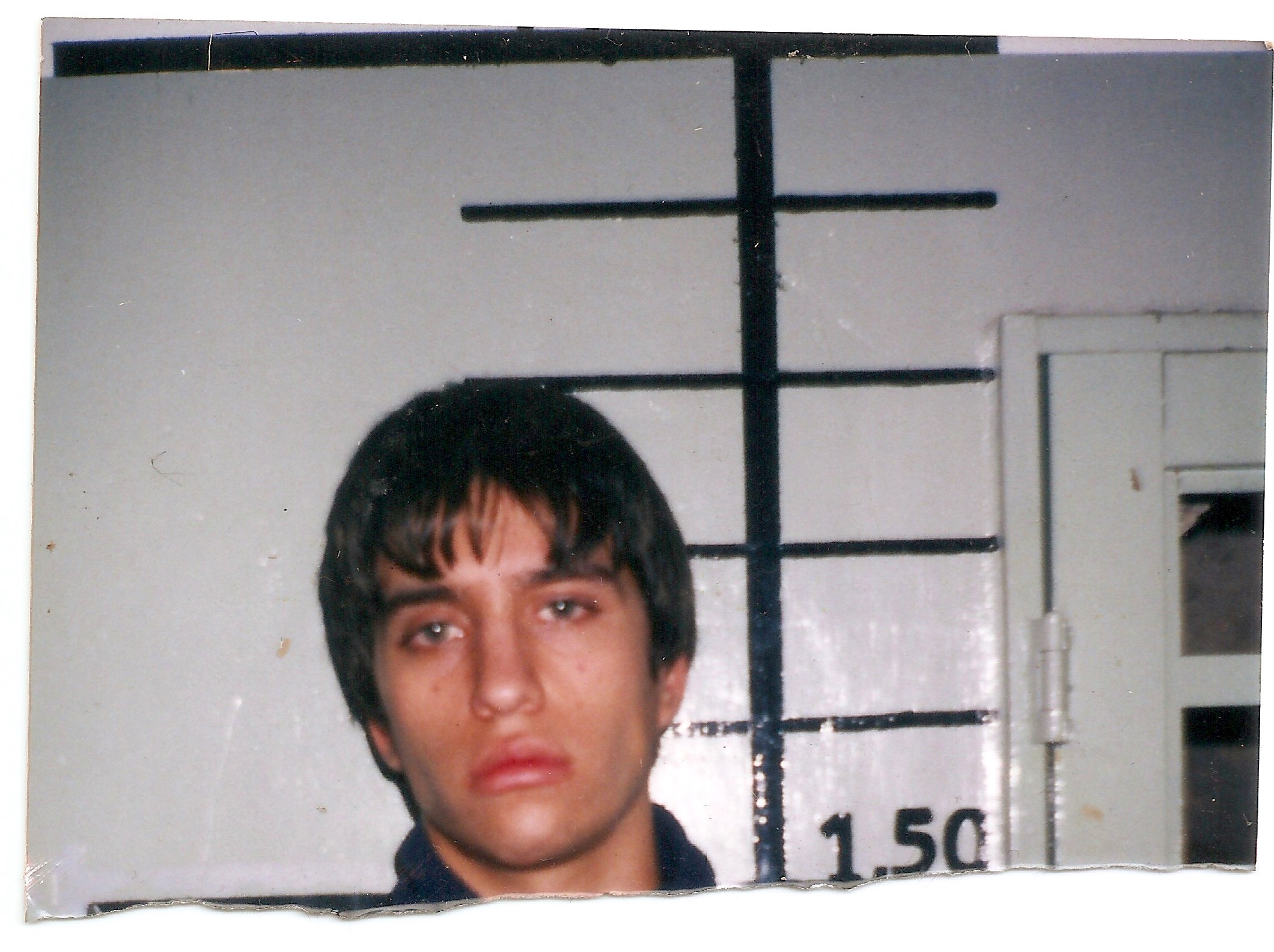

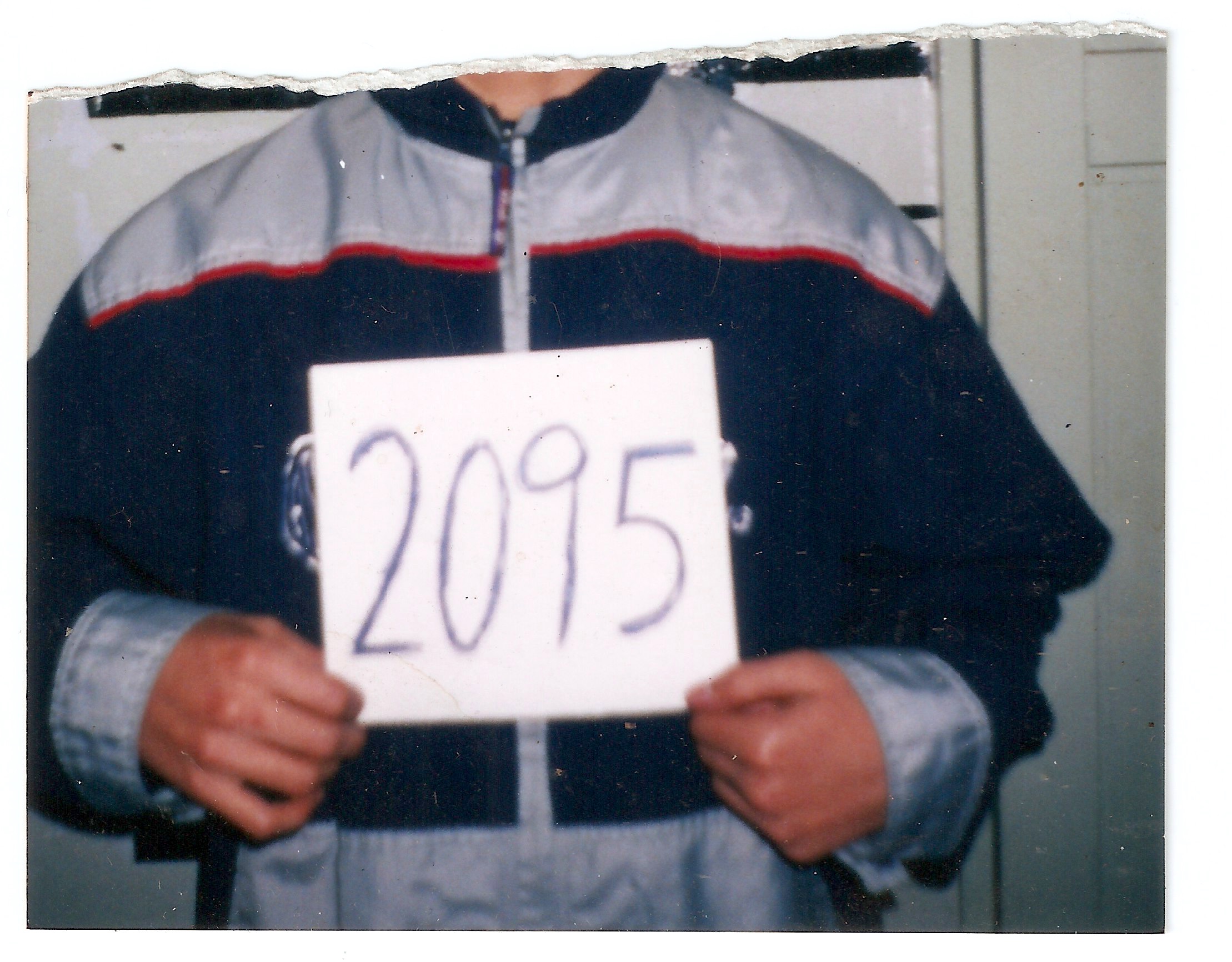

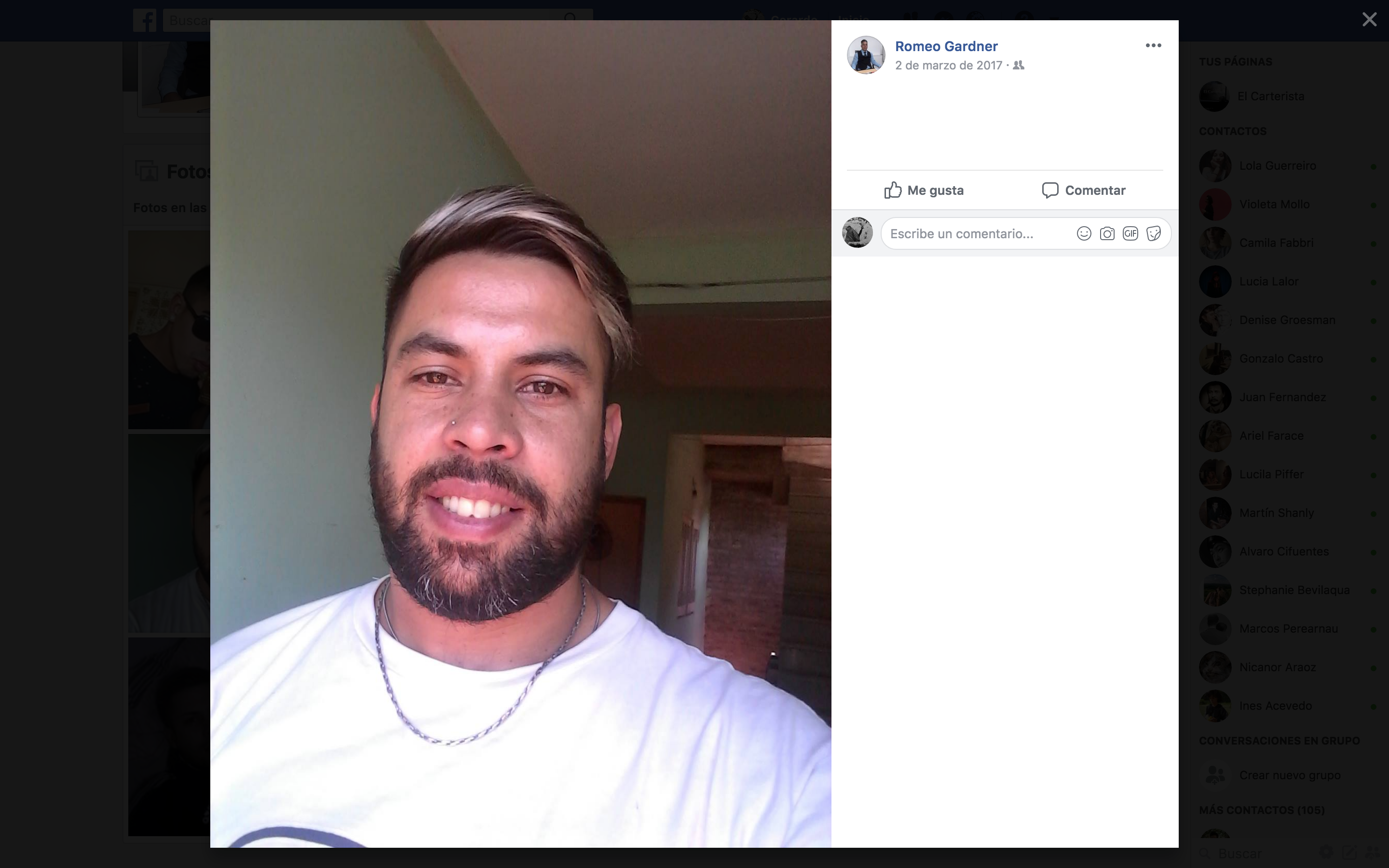

Maxi gives me the contact information for his brother-in-law Romeo. Romeo was in jail for a number of years. He tells me to call him. I look him up on Facebook and find this.

September 1

The Pickpocket is shown a couple of time in the gallery. I am not convinced by the results. It lacks precision. I discover the problem of precision more so here than in the pieces dedicated to work. Unlike The Factory in which the works respond to the precise time of the machine, here there is no machine, or it is something else. If the transmission from Toc Toc is not precise, the play does not get told. If the travel time is too long and the play has to be stretched out so it connects with the beginning of Toc Toc, there is something we are doing wrong. In the work the machine is there; in the robbery I am alone.

I am thinking about The Lizard. He is tall and his head sticks out. Julieta calls him to arrange for a second meeting. He doesn’t answer his cellphone. His wife does answer. The Lizard’s wife is like his secretary, but she isn’t his secretary. She doesn’t see herself like that. He doesn’t put herself in that role. She answers the calls a bit against her grain. She curses, but is helpful. She says that The Lizard will get home at night. He went to make some delivery, she says. The story is very vague. Not understandable. He has a moving truck, or drives one. Or has some parts of a moving truck. I think about the parts, that vagueness. Vague stories. Not hard and clear, but rather vague, nebulous.

September 12

Julieta tries to speak with The Lizard. Then again to his wife. It is difficult to understand where he is. She herself doesn’t seem to completely understand. It seems that he was offered some substitute job as a security guard at a company. It seems that he was making a delivery and they offered him the job and he stayed there. The Lizard’s story, not the one he told me, but the one he created for everyone, including for his wife-, is a story without cause or effect. It goes from one point to another. There is no idea of continuity. The form of the story makes me think of childhood. I am here and then I am there. Woooosh! I went from one place to the other and I don’t even know how!

September 19

At the jail with German. Today is Monday, the beginning of the week. The weekends are difficult. They want to leave. Here leaving is double leaving. Leaving from there and leaving,leaving to go out dancing, to have a drink. On Mondays, you can the work of beinga prisoner. They work at this all the time. Monday and Mondays for them as well.

I call Romeo, Maxi’s brother-in-law. We arrange to get together.

September 20

Places. I think about the spaces where I was mugged. A corner in the neighborhood of Almagro, at night. I’m with Rodrigo. Crossing the street. A guy on a motorcycle stop and asks us for a street with a name that we don’t understand. We are drawn in. Then the mugging happens. The guy acts like he has a weapon and threatens us. We are startled and give him our wallets and cellphones. The place is wide open. He is sitting on a motorcycle. Running away is easy, but it doesn’t occur to us. It is as if the guy close had close in the place. He sets the closed up in the open. I see it related a little bit to the guys who put on theater at the corner of Florida and Lavalle. Clearly, there is a circular stage functioning here. I am not sure what is the center, but it seems like it is our wallets and cellphones.

I took this photo in Rodó Park, Montevideo. In that which is circular, there is a center.

September 22

The jail returns with clarity over this man-woman myth. Men inside, women outside.

September 24

Relationship of the criminal prisoner with waiting. The prisoner waits to leave; those outside wait for the prisoner. Places that the criminal leaves in waiting: a house, a family, a job. I think about the return to the thing that waits. The return.

September 16

I meet Romeo on the corner of Maipu and another street, in Vicente Lopez. We walk to the cost of the river. On the bank we sit on some rocks and look at the water. He tells me about his years as a criminal. He likes weapons. Nothing calls to me that much. I think about Kafka’s text about tree trunks that seem to be moving in the snow, but aren’t. They are caught there and that too is just appearance. I don’t know why I think about that. Kafka is, for me, someone from the past and from Prague. Prague and Kafka are ideas. Both understood that. Prague as well as Kafka. The criminal as well as the actor know this: ideas are never things.

September 18

The Lizard disappears. He doesn’t answer his phone. His wife doesn’t know when he is returning, nor when he left. There is no strategy there. You have to be in movement.

I think about my childhood in the countryside. Movement, yes, but with the earth solid beneath your feet. The owner of the earth steps upon his land. The earth does not go away, does not evade. There is no over there. Over there is everywhere. The Lizard does not have over there, he looks for it. He moves.

In Ezeiza, German is detained. He cannot move. He is not the owner of the earth that is under his feet, nor can he leave from over there. Acceleration in leaving, I think. Stumbling block.

October 13

A record of Morton Feldman. Feldman is a problem of scale. The criminal like being without scale. Again, the idea of the infantile.

Actors. I don’t know who to call. I think about actors from Buenos Aires and none of them seem right. For me the actors from Buenos Aires are too close to the television channels. Every now and then they slip into the television studies and leave all wet.

October 18

Conversation with Dani Elias on Skype. I only saw Dani live once. The other times I saw him in movies. Seeing him on Skype is like seeing him in a movie, filmed with a poor quality camera.

Dani lived in my house for a while when I was on tour with The Factory. At one point when he was passing through Buenos Aires I met him. We went to see something at the di Tella[2] and then we went to eat. At the di Tella, Dani drinks wine all the time. That day in the di Tella, I think about us working in the silo. Dani tests the limits of the context. He does it with an action: that of drinking wine all the time, standing, sitting and walking. In art spaces, on the days of openings, people drink wine. Meaning, that the context accepts the action. But Dani does not stop. He buys another glass, puts it underneath the poncho he uses, walks, smokes, shares, makes little toasts, and goes back. With the insistence of his action, the framework appears, the University of Art, the institution. It is like the group of us making the silo. It is fun because we are saying it over there, saying it by repeating that action. Dani knows this.

During the Skype, he sends photos to my cellphone. The channels of communication multiply. There is surreptitious life.

October 20

The jail of Ezeiza. I chat with German who spends the time smoking. But it seems like someone else is smoking, not him. He, of quiet movements, a slow gaze, does not seem to be smoking. Someone who is inside the jail is smoking. He says to me:

You don’t rob just once. Robbing begins at the second one. I read my diary, the entry from March 12, 2015, in which I rob the image of the woman in the National Library two times.

November 1

I meet Giusti in Bar Roma. He arrives with someone he presents as his friend, but we realize that he is his bodyguard or someone who is with him. Since leaving jail, he has been dedicating himself to the music business. His son is number two in Chile with a song that he shows us on YouTube. The song – a young Reggaeton – is not very good and it seems like Giusti is a bit embarrassed about it, but not that much.

About a half hour into the conversation, he names Juli, The Greek. He practices conquering her, making a foundation. Giusti is pure moving forward. He dominates the conversation. He interrupts. He pays. What destabilizes him is not having control.

The criminal as a way of installing order in a new territory.

November 5

María reads about a guy who was in jail for several years, made a short film and, -once out of jail-, traveled to a number of film festivals. She calls the newspaper and asks to speak to the journalist who wrote the article, and ask him for Mario’s phone number. I meet with Mario in a space that he set up, in a shantytown. It is a space where they hold recreational activities, offer help with school work, give snacks, etc. Mario tells me about his years in jail. At one moment, we go up on a moment mountain of earth that is in front of the place he is directing. From up there, we can see the roofs of the houses. He tells me he wants to make an amphitheater over there, in the slope of the mountain of earth. Seats looking at the neighborhood from above. The actors acting on the roof of his space, just below. Mario seems to be recycled, to have self-recycled. Mario gives me the telephone number of Hernan, and that of Waldemar.

November 8

I meet with Hernan. We meet at a rationalist bar in the greater metropolitan area. I took this photo of him in the bar. He arrives on a motorcycle and rubs his eyes, like someone who just woke up. He says that he was framed and that’s why he became an inmate. He was arrested for trafficking narcotics. We talk about food. He says that his favorite food is meatballs. He invites me to eat at his house. Of course, everything is fine. Easy to integrate. No does not exist. Hernan has a coffee with milk and eats two medialunas (croissants). The last cold days of the year. The summer is ahead. We both know it and we don’t say a thing.

November 10

Waldemar. Everyone calls him Wali. Second meeting at his house. Wali says that he could have escaped from the shanty town. His house is a block from the beginning of the Cárcova, that he says, is the largest shantytown in Latin America. All the time, he is telling me what it means to be a prisoner, his identifying mark. The criminal finds that upon leaving the jail his identity is that of having been an inmate. The identity tumbera. There is, I think, with this stigmatization, a stumbling block. We are uncomfortable with Wali in his house. We are sitting at his table, stuck. I want to leave the place, lighten things up. I ask if he will accompany me to the station. From his house to the station is a 40 block walk. On the way, things soften. We say hello to people that pass by. During the course of things, I decide that Wali is going to act in the play. I have to wait for what needs to soften up, to soften up. What kind of an actor will he be? There is something I am never going to tell him. If one day this is published, I will erase it.

I took this photo the other day, in the mirror of my bathroom in my home in the neighborhood of Once.

Waldemar.

November 11

I find a photo of a tunnel that I took once returning from Uruguay. The feeling of traveling with others.

Encuentro una foto de un túnel que saqué una vez volviendo de Uruguay. La sensación de caminar entre otros.

November 15

Attentive to a sentence that Luciana Lamothe says all the time. You have to try.

November 22

The Lizard calls me on the phone. He says he is sorry for not calling before. I tell him not to worry, that I knew he would call. When I hang up, I think that I knew that The Lizard was going to call me. The criminal as an engineer without a plan, the engineer of confusion and disorder. But an engineer all the same.

October 23

Return to see Romeo. Again, we walk from the avenue to the bank of the river. We walk by beautiful houses, little chalets that look at the street from behind iron fences, barbed wire, some of them electrified, others not. I think about what he is thinking. Romeo looks at me. He is thinking about what I am thinking. Or I am thinking that he is thinking about what I am thinking.

On the bank of the river. Nearby the boats, the sailboats. Romeo tells me about assaults. He tells me about when they entered a house and there was a person. They took food from the person’s refrigerator and throw it in the person’s face. What startles is what belongs to one. I am fear.

Romeo asks for an ice. Strawberry, he says. He runs his tongue over it and looks at me and smiles. He has very large teeth and a big smile. The sun reflects off the tip of a wind surf board.

Attraction for the criminal mind. Everything is in the mind. Buy self-help books, books about mind control.

November 24

From Pedro, the first thing they do is give me a book. It is called My Life as a Criminal. Here is a photo of his book on sale in “Mercado Libre”. I read it in an afternoon. In the case of Pedro, first I hear his voice in the book and then I hear his voice in reality. It is the same as the day I heard the voices of the prisoners, first in the psychiatrist reports and then in reality. I think about the anticipation of voices. To know something about someone, hear the person’s voice, before seeing the person. Pedro’s voice, the voice of Pedro’s book, is different from the voice of the thief, as it is known through the media. The most important thing about the piece is the voice. That they speak.

Atento a una frase que Luciana Lamothe repite todo el tiempo. Hay que probar.

May 8, 2017

They call Pedro, Bambi. He says he saw the film more than 30 times. When he was in jail a friend had the DVD. In the rehearsal, I ask him if he wants to show me the Bambi he has tattooed on his back. He shows it to me. I propose to him that we go to Sierra Chica, the jail where he got the Bambi tattoo. He agrees. I don’t have a very clear plan. We go in the car with Dani and Juli. It is more than 400 kilometers away. Bambi looks at everything. He makes comments, but at times he doesn’t. There are things that he says nothing about. I try to understand his system of speaking or being silent.

When we get there, we sit down at a restaurant. He asks for wine. Bambi tells us about the day he got out of jail. He tells us about the people that he saw after so many years of being in a prisoner. We leave the restaurant. The faces of the people in the street. We take photos of the people walking by. Reconstruction, but clearly phony. Anti-reconstruction. Anti-history.

We go to the jail. It is about 40 kilometers from Olavarria, in the middle of nowhere. The walls are made of stone and are black. From the sentry booths on the walls they are looking at us with binoculars. They see suspicious movements. Bambi says that they can arrest us. I ask him to take off his t-shirt. We take a photo.